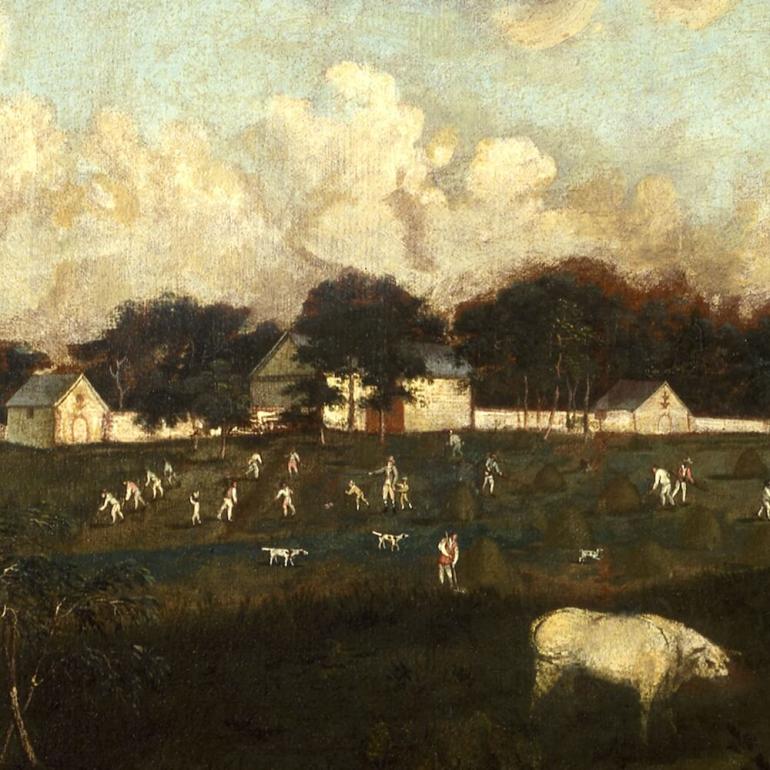

Enslaved field hands in rough-hewn woven clothes working in the fields near their quarters at Perry Hall, which became a Carroll property through marriage. Painting by Francis Guy, circa 1805. Courtesy of the Maryland Center for History and Culture.

Enslaved People

Enslaved people held by the Carrolls did not leave written records. Most of the information we have discovered about their lives come from letters written by the Barrister or his father, or from business records like wills and inventories. The average Maryland family held three enslaved people. Charles and Margaret Carroll held more than 70 people at their various properties, and more than 200 enslaved workers toiled at the Baltimore Iron Works.

The experience of enslavement varied greatly among the Carroll properties, depending on the season, labor performed, size of slaveholding, and gender of the person. Jobs were hierarchical, as were clothing, food, rations and quarters. Most slept at their stations, including stables, kitchen, wash house, basement, and sheds and were on call 24-hours a day.

House Servants and Livery

To reflect his wealth and social status, the Barrister ordered lavish uniforms made in London for his house servants, coachmen and grooms. They wore green livery trimmed in scarlet. House servants helped dress and bathe the Carrolls and served elaborate meals handling the Carroll’s expensive export china and silver.

Originally, this jacket was believed to have belonged to Charles Carroll, Barrister circa 1770. But on closer inspection, curators determined this was livery for an enslaved house servant circa 1840. Livery was deliberately made to look anachronistic to identify the enslaved. Courtesy of the Maryland Center for History and Culture.

Workforce Clothing

Clothes production for the general workforce was handled by enslaved men and women at the various Carroll properties. They undertook each step of the process from growing flax, spinning thread, weaving and dying cloth, sewing garments, and making bone or shell buttons. A 1773 letter states that an enslaved weaver named Moses, who lived and worked at the The Caves plantation, required 8 to 10 hand spinners to supply him with thread.

The majority of the enslaved wore clothes made from osnaburg, a rough woven cloth similar to burlap, that was dyed blue to indicate enslavement. Osnaburg fabric was probably first imported to England and its colonies from the German city of Osnabrück, from which it gets its name.

Laundry was a particularly labor-intensive job requiring a constant cycle of soaking, scrubbing, buckling (a bleaching process using lye from ashes) beating, drying, and ironing. Underclothes and linens were washed, outer clothes were spot-cleaned.

Agricultural Work

Field hands and gardeners wore undyed osnaburg clothes and worked from sun up to sun down. Field hands toiled in the tobacco fields, grain fields, and vineyards. They also managed the livestock, including dairy cows, sheep, pigs, and chickens. Gardeners worked in the ornamental and kitchen gardens, orchards, and greenhouses where some slept in order to keep the fires burning all night.

Iron Work

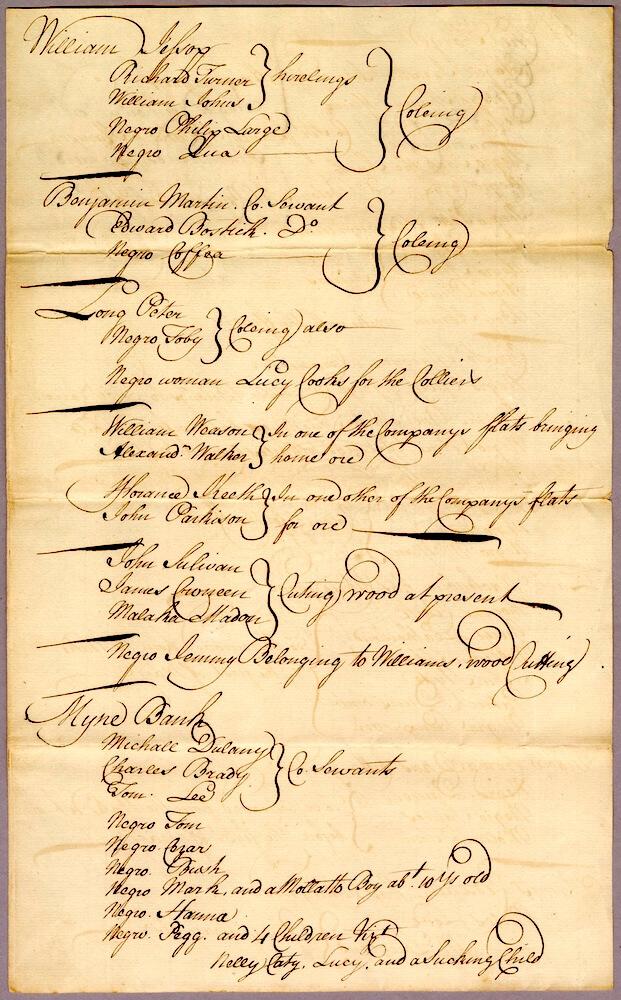

At the ironworks, enslaved laborers in undyed osnaburg clothes worked 12-hour shifts at the blazing hot furnace. Initially, the enslaved were used in unskilled positions like carting loads of raw material to the 35-foot stack, but quickly the enslaved were trained in all the skilled positions too. Many brought knowledge of metalworking from their homelands. Enslaved laborers also worked at different Carroll properties throughout the year, collecting raw materials - including iron ore, limestone, timber, and oyster shells - needed for iron production. Enslaved women worked as cooks at the ironworks and as miners, along with their children, picking out iron ore and limestone from shallow pits.

As soon as ye Can conveniently do it to get Young Negro Lads to put under the Smith, Carpenters, Founders, Finers & Fillers as also to get a certain number of slaves to fill the Furnace Stock the Bridge Raise Ore & Cart and burn the same. Wood Cutters may for some Time be hired there. There should be Two master Colliers one at the Furnaces another at the Forge with a Suitable Number of Slaves or Servants under Each who might Coal in the summer and Cut wood in the winter.

Dr. Carroll in a letter to a potential furnace owner advising him to train enslaved workers for all the skilled positions, 1753.

Food

At most work sites, including the ironworks and coal-making sites, enslaved women cooked a common meal for all the workers. At the ironworks, the cooks were given rations of corn, salted pork, beef, and molasses to feed workers. Enslaved people at the other plantations typically received weekly food rations from an overseer. No records have been found detailing the rations that the Carrolls allotted for their enslaved, but typical weekly rations from a southern plantation included one peck of corn (about 14 pounds), 3-5 pounds of bacon, a half pint to a quart of molasses and possibly some bread, peas, potatoes, or milk. Josiah Henson, a former enslaved man born in Maryland, whose memoir inspired the novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, described his rations of corn meal, salt herring, and buttermilk. Typically, children were not allotted food rations until they reached eight, the age at which they began working in the fields, tending farm animals, doing housework, running errands, or babysitting.

The enslaved were expected to supplement their diets in their scant free time by fishing, hunting, and trapping, as well as raising chickens, and growing vegetables in small garden patches near their quarters.

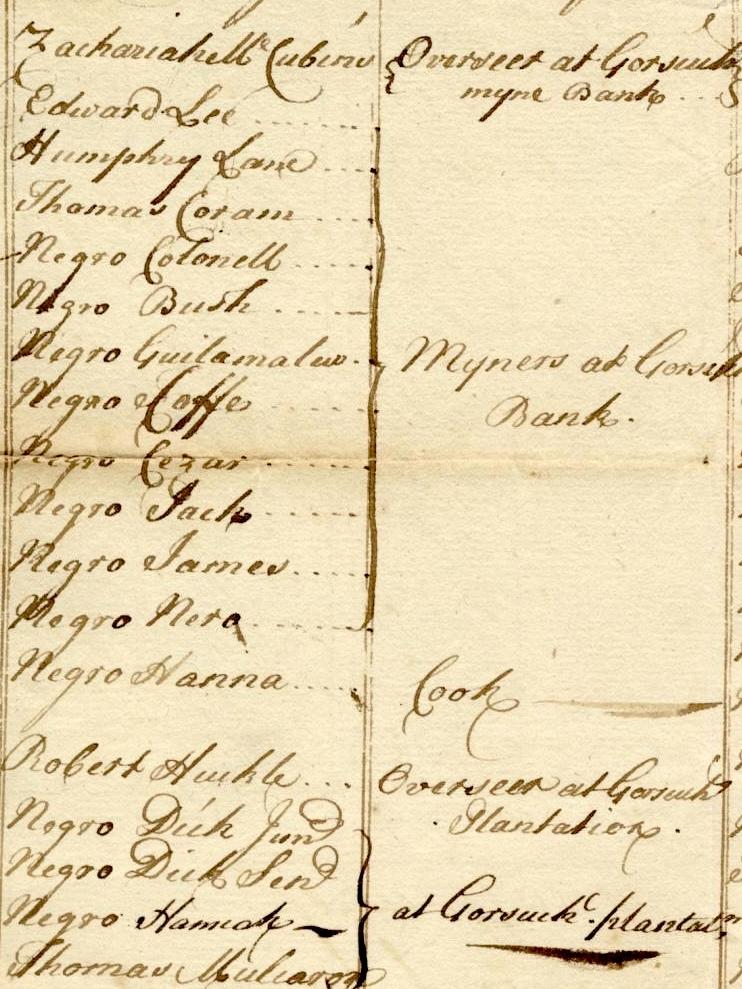

List of hired hands and enslaved workers who were sent to Gorsuch’s Plantation, a 500-acre tract in today’s Canton section of Baltimore, that was purchased by the Baltimore Iron Works in 1733. Note the enslaved woman named Hanna assigned to prepare meals for the workers there. Courtesy of the Maryland Center for History and Culture.

Comparison of yearly rations for Enslaved Laborers at Chesapeake Ironworks.

Skilled | Unskilled | |

Pork | 300 pounds | 225 pounds |

Corn meal | 20 bushels | 13 bushels |

Osnaburg | 12 yards | 7 yards |

Summer suit | 1 | 0 |

Winter suiting | 7 yards | 0 |

Leather shoes/Boots | 4 pairs | 1 or 2 pairs |

Socks | 1 pair | 1 pair |

Hat | 1 | 0 |

Study by Swedish scientist Samuel Hermelin comparing food and clothing rations between skilled and unskilled enslaved laborers at Chesapeake ironworks, 1783.