Miniature of Mount Clare, attributed to artist Guy Frances in a settee by Baltimore furniture makers John and Hugh Findlay, circa 1804. Courtesy of the Baltimore Museum of Art.

Georgia Plantation

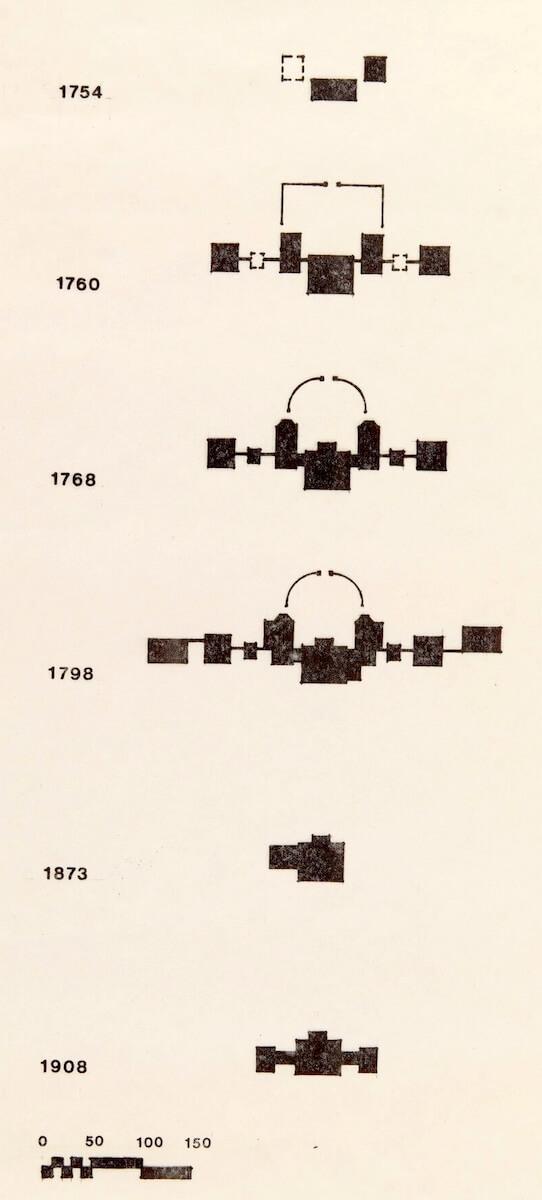

While accumulating land between 1729–31 for a new business called the Baltimore Iron Works, an enterprising Irish immigrant and physician, Dr. Charles Carroll, kept an adjacent parcel for his own use. He named the 800-acre tract Georgia Plantation after the reigning English king. Sometime around 1750, he had a modest, one-and-a-half-story bachelor house built here, likely by enslaved laborers, for his 22-year-old son John Henry. The young man died suddenly of consumption in 1754, followed a year later by Dr. Carroll. Ownership of Georgia Plantation passed to Dr. Carroll’s oldest son and namesake, Charles Carroll, Barrister.

Country Seat

Interested in building a summer home, known as a country seat, that reflected his social status, political power, and wealth, Charles Carroll, Barrister, replaced the modest structure with a more substantial center block Georgian mansion from 1756–60. His builders very likely included unpaid enslaved and indentured workers as well as hired hands. He ordered window glass, sheet lead, hinges, locks, and nails from England, and sourced nearly everything else from Annapolis merchants. He named the home Mount Clare to honor his sister Mary Clare Carroll Maccubbin, and their grandmother Clare Dunn Carroll.

Grand Entrance and Hidden Staircase

Less than a decade after Mount Clare’s construction, the Barrister and his wife Margaret Tilghman Carroll embarked on a major renovation to incorporate the latest European architectural developments. Between 1767-68, they added a grand, two-story, Neoclassical entrance portico with Doric columns and a Palladian window. Octagonal, two-story wings, containing the Barrister’s office on one side and the kitchen on the other, pushed out from the main house, creating a forecourt and giving the formerly flat, static house depth and the illusion of movement.

One of the curved or ogee-shaped hyphens connecting the wings to the house concealed a servant’s stairwell that enabled enslaved and indentured workers to move from the service areas to the house without being seen. This was the first documented servant’s staircase in Maryland, and the concept was imported back to England where it was widely adopted.

Inheritance

A day after his 60th birthday in 1783, the Barrister passed away. On his deathbed, the childless Barrister left his estate to two of his sister’s five sons, Nicholas and James, provided they would take his surname. While she did not inherit the properties, Margaret was given life use of several houses. She chose to spend her time at Mount Clare and a small house at another Carroll plantation called The Caves.

Margaret remained at Mount Clare another 34 years, outliving the eldest of her husband’s heirs, Nicholas Maccubbin Carroll. She continued to maintain and update the house and gardens with enslaved workers and hired hands.

In 1790, the west wing was completely consumed by fire, but Margaret had it rebuilt. In 1798, she oversaw renovations that incorporated the new Federal style. Margaret turned the plantation office into a drawing room, changed the attic window from a circular bull’s eye to a lunette. She also added additional servant’s passages as well as a large pantry or enslaved quarters off the east hyphen.

Margaret died in 1817 and planned through her will to free the 49 enslaved people whom she held at Mount Clare and The Caves. However, the two nephews who served as her executors resold 34 of those individuals under delayed manumission, designed to grant them freedom once they reached certain ages.

Encroaching Industry

After Margaret’s death, the Barrister’s nephew and heir James Maccubbin Carroll moved into Mount Clare with a new group of enslaved workers. A widower with grown children, he embraced the industries sprouting up around Georgia Plantation. He rented his fields to brickmakers to mine clay and gave the fledgling Baltimore & Ohio Railroad the right-of-way to construct the country’s first commercial rail line across his land. He also gifted a total of 25 acres of plantation land to the B&O to construct their first station and maintenance yard. He remained at Mount Clare until his death in 1832.

Last Carroll Residents

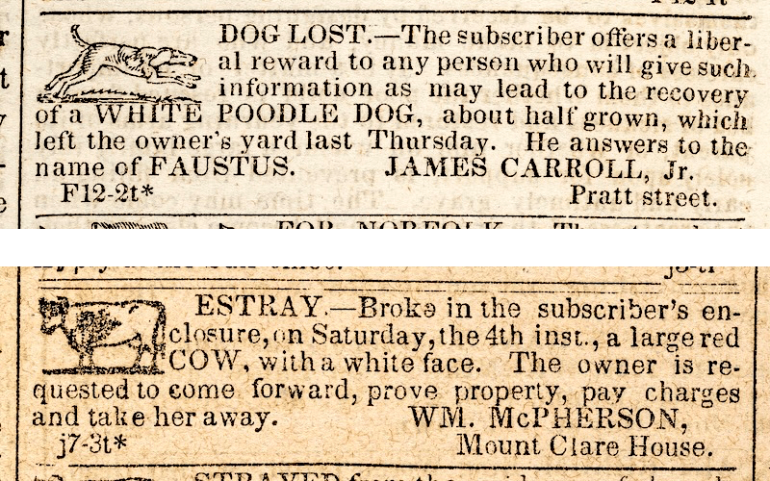

The third and final generation of Carrolls to live at Mount Clare was the family of James Carroll Jr., the son of James Maccubbin Carroll. His young family and the enslaved laborers they held lived at Mount Clare less than four years. Weary of the increasing industrialization around Georgia Plantation, they moved to a house on Baltimore’s Pratt Street around 1836.

The Carroll family rented out the property to a series of hotel operators. During the Civil War, two Union camps were built on plantation lands. Later a group of German immigrants rented the house and surrounding grounds for use as a private club. They got permission to demolish Mount Clare’s then-dilapidated wings and outbuildings and build a two-story kitchen.

In 1890, Carroll descendants sold the house and remaining grounds to the City of Baltimore for $45,000 for use as a public park. In an effort to restore the colonial architecture, the City built modest, one-story wings and hyphens in 1908. These served initially as offices, but were quickly converted to public bathhouses for the park.

Museum House

Originally, the Carroll Park Director lived in the mansion, but in 1917, the empty house was turned into a museum under the stewardship of the National Society of Colonial Dames of America in the State of Maryland, or NSCDA-MD. They spent years researching and collecting original Carroll family and period pieces to furnish the museum.

In 1960, after the bathhouses ceased operation, these wings were converted to a library and colonial kitchen and added to the museum. Archaeological investigations during the 1980s uncovered the foundations of the original office and kitchen wings, as well as the forecourt. These have been reconstructed and filled with gravel to delineate the footprint of the original wings.

Beginning in 2018, the museum has undertaken a comprehensive reinterpretation to tell the story of all who lived and worked at Mount Clare and the industries that supported it.