The Port of Baltimore was long a backwater town with roughly 200 inhabitants, 25 houses, one church, two taverns, and one brewery. Engraving by William Strickland in 1817, based on a 1752 sketch by John Moale. Courtesy of the Maryland Center for History and Culture.

From Sleepy Backwater to Major Port

Situated far from the tobacco fields of southern and eastern Maryland, Baltimore harbor saw sparse traffic until a local merchant started shipping flour to Ireland in 1754. Suddenly, Baltimore’s potential as a shipping center, so close to the wheat producing areas of southern Pennsylvania, became obvious.

With ample water power provided by Baltimore’s three major rivers, Gywnns Falls, Jones Falls, and the Patapsco, Baltimore became a became a boom town for grain processing and export. Grist mills were hastily constructed throughout the region.

Ahead of the Curve

Before embarking on building the ironworks in 1731, Dr. Charles Carroll had two grist mills constructed, likely by enslaved laborers, on Gwynns Falls. As a result, he was well situated to capitalize on Baltimore's new-found role as a grain processing center.

The Carrolls sublet their mills to white millers who probably used a mix of enslaved workers and hired hands to grind grain brought in by neighboring planters. The Carrolls also owned a bakery in Annapolis, which they supplied with flour. The grist mills provided a steady source of income for the Carroll family and operated more than 150 years.

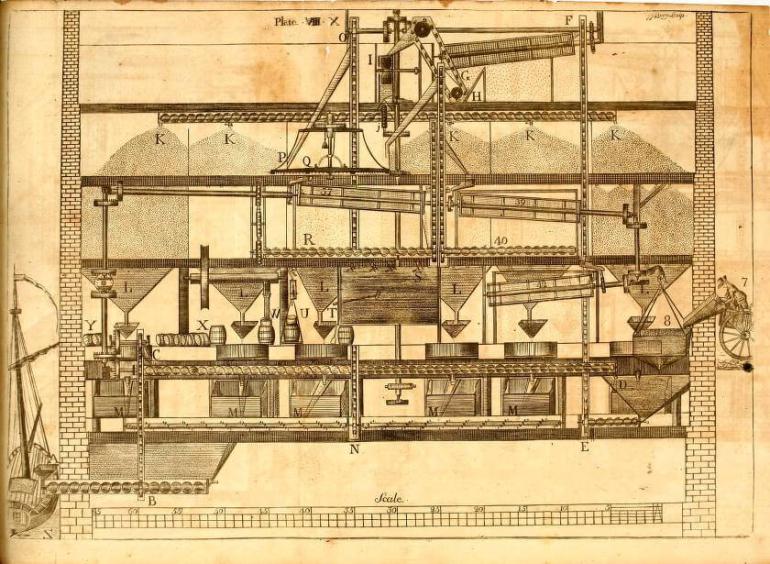

Designs from a 1795 book on mill construction by American inventor Oliver Evans. The Ellicotts, a Quaker family in Baltimore who owned the Ellicott Mills, and George Washington were early adopters of his innovations and hired him to mechanize their flour mills. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Early Environmental Precedent

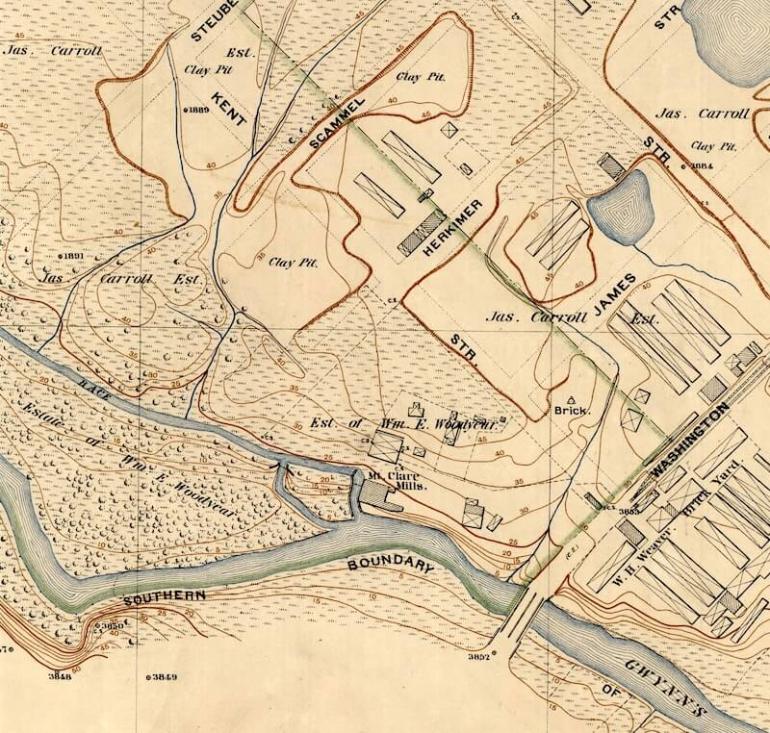

Carroll descendants sold the lower mill, known as Mount Clare Mill, to William E. Woodyear in the late 1870s. By this time, Gwynns Falls had become badly polluted by hair manufacturers, soap boilers, brewers, and butchers. In 1881, Woodyear successfully sued a meat packer upstream to prevent him from dumping waste in the waterway. The case set an early and important legal precedent for future environmental cases.

Disappeared Under the Interstate

A 1911 insurance atlas of Baltimore shows that Mount Clare Mill’s machinery had been removed by that time. The building quickly fell into ruin after that. Only the west dam abutments remained in 1975 when the I-95 interchange was built near it. Today, there is no visible trace of the mill along the Gwynns Falls trail next to the Carroll Park Golf Course.

Served through Three Wars

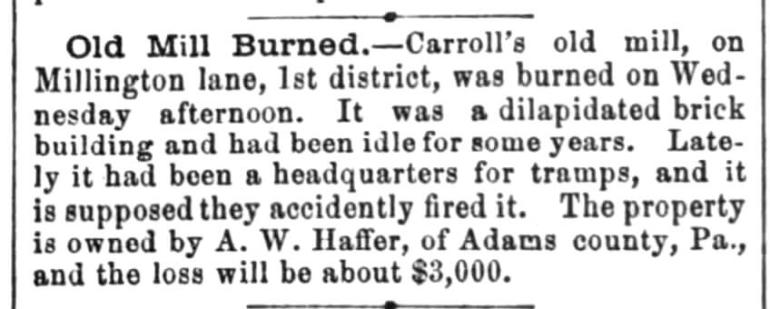

The Carroll’s second grist mill was on the east bank of Gwynns Falls and was known as Millington Mill. It was impacted, most likely deprived of water, by the Baltimore Iron Works. Dr. Carroll complained to his partners, but they refused to compensate him.

It was active for nearly 150 years, operating through both British Wars, the American Revolution and the War of 1812. During the Civil War, a Union encampment called Camp Millington was built near the mill. The structure had been vacant for several years when it was accidentally destroyed by fire on April 29, 1885.

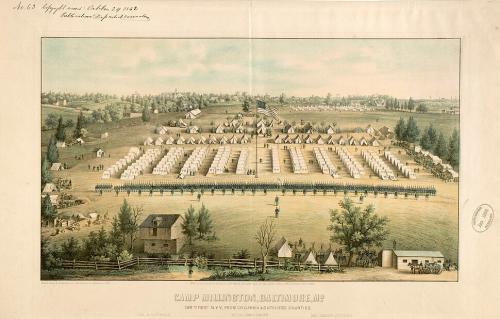

Bird’s-eye view of Camp Millington in Baltimore, Md, housing the 128th New York Infantry Regiment from Columbia and Dutchess Counties, by E. Sachse & Co., 1862.