Bethlehem star on top of the Sparrows Point ‘L” furnace c. 1979. The furnace operated from 1978 through 2013. Courtesy of the Baltimore Museum of Industry.

From Baltimore Iron Works to Bethlehem Steel

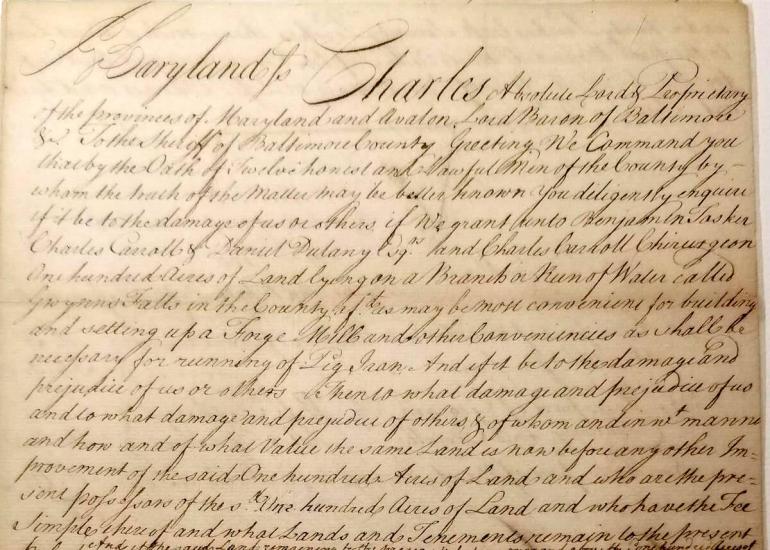

Endowed with rich iron ore deposits, abundant timber, and navigable waterways, the Baltimore region sustained a long history of iron and steel making. During the colonial period, iron was needed for constructing ships, buildings, weapons, and tools. The Baltimore Iron Works, which operated from 1731 to 1799, was the second iron operation to be organized in the colony, but the first to be locally owned. British investors had established The Principio Company in 1719 in Cecil County.

For nearly 150 years, the primitive but effective cold-blast furnace technology was used by a succession of 13 companies in Baltimore County to manufacture iron. However in 1889, a small firm at Baltimore’s Sparrows Point began producing a stronger, more versatile alloy called steel. By 1954, the Sparrows Point mill, then owned by Bethlehem Steel, was the largest in the world. Its dominance would not last. Technological advances and foreign competition forced it into bankruptcy by 2001. Today, the former steel plant is a distribution center for retailers like Amazon and Under Armour.

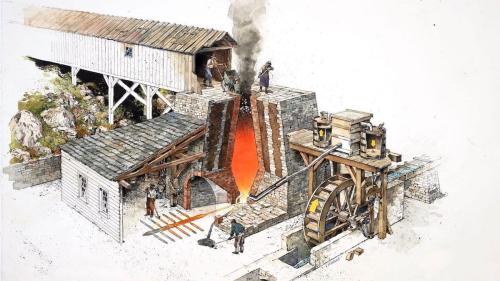

Ironworkers guide molten iron flowing from the furnace stack into pig iron molds. Courtesy of the National Park Service.

Diversifying into Iron

Five wealthy and politically-connected planters looking to diversify away from tobacco founded the Baltimore Iron Works in 1731. Dr. Charles Carroll, a surgeon and Irish immigrant, contributed 2,200 acres of resource-rich land on the middle branch of the Patapsco River and served as the first company manager. The other partners, his distant cousins Charles and Daniel Carroll, Daniel Dulaney, and Benjamin Tasker, provided money and enslaved laborers.

Treacherous Work

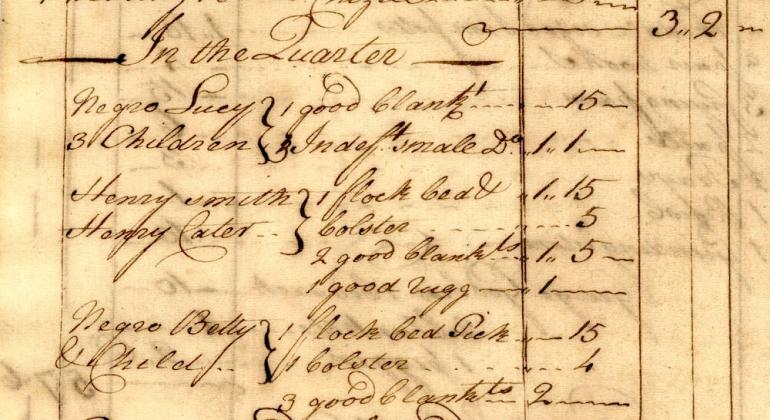

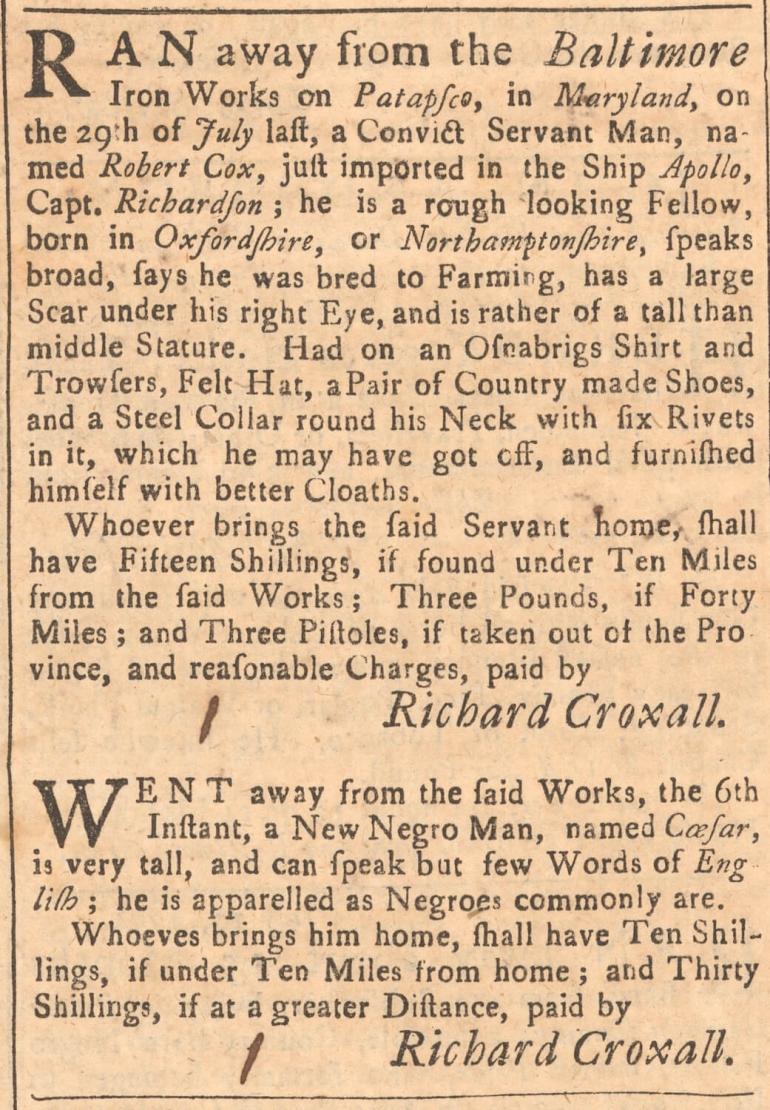

Manufacturing pig iron was dangerous, back-breaking work amidst deafening noise and intense heat. Laborers, many of whom were enslaved or transported convicts from Britain, worked 12-hour shifts hauling cartloads of charcoal, oyster shells, and iron ore to the top of the furnace while molten metal flowed into sand molds at its base. Production continued around the clock, six or seven days a week, for as long as raw materials were available.

Resistance and Cooperation

Many enslaved and convict laborers resisted the brutal conditions. Some ran away, others worked slowly or carelessly. The risk of poor-quality iron or sabotaged equipment prompted the company to incentivize workers. The ironworks opened a company store and gave credit to their skilled workers if they met or exceeded work quotas.

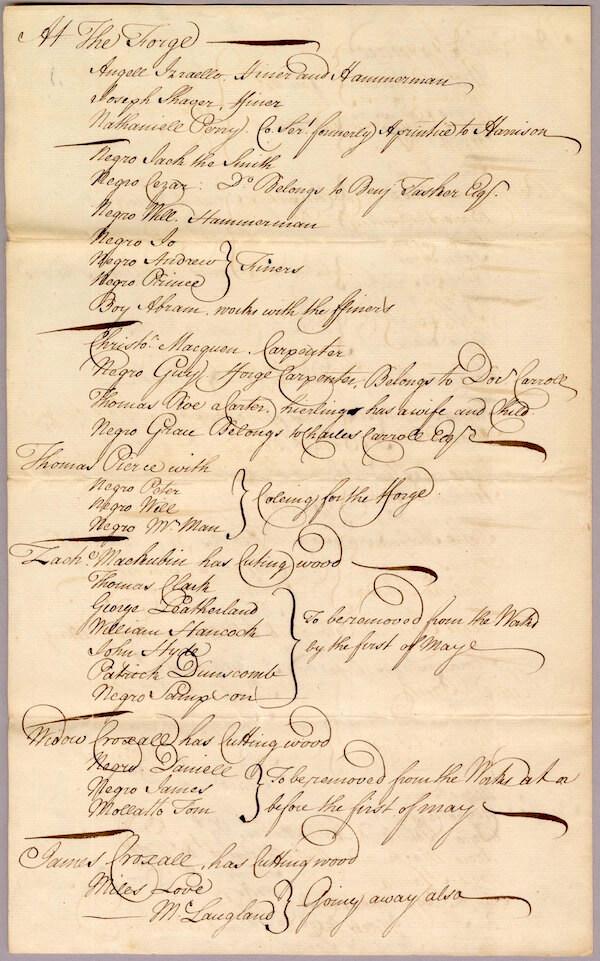

Highly Skilled Workers

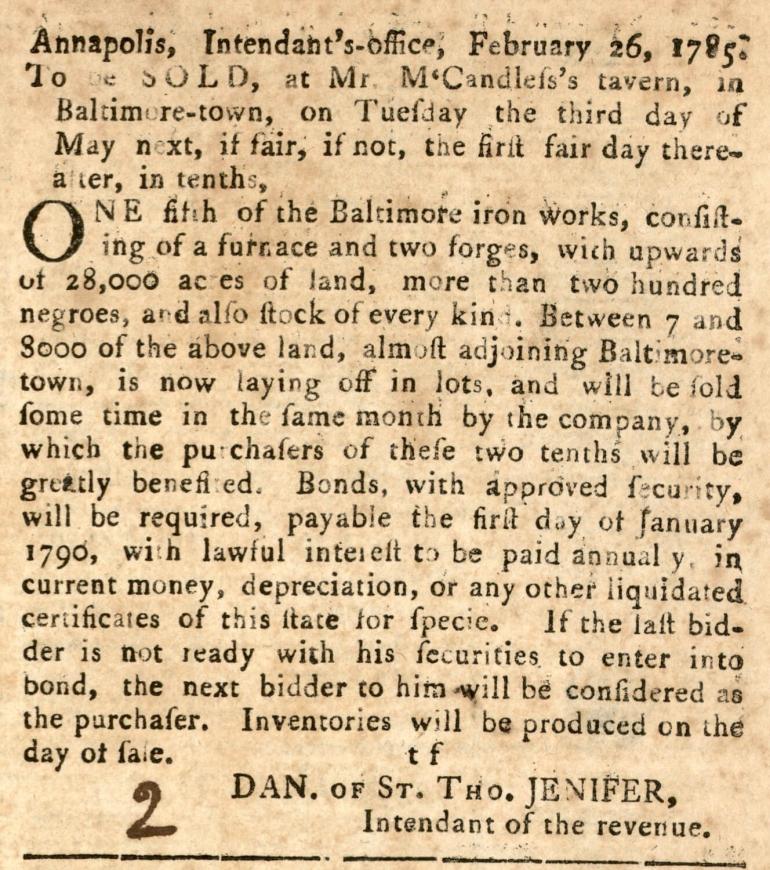

The Baltimore Iron Works opened with a workforce of 89, including 42 enslaved individuals. By 1785, it advertised a workforce of “more than 200 Negroes.” Colonial ironmasters realized that many of the enslaved were of the Igbo culture and brought vast metal working experience from their homeland. The ironworks managers preferred enslaved laborers, whom they felt were more reliable than transported convicts. These highly-skilled, enslaved ironworkers received more food and clothes rations, as well as better living situations than unskilled, enslaved laborers.

Lucrative Venture

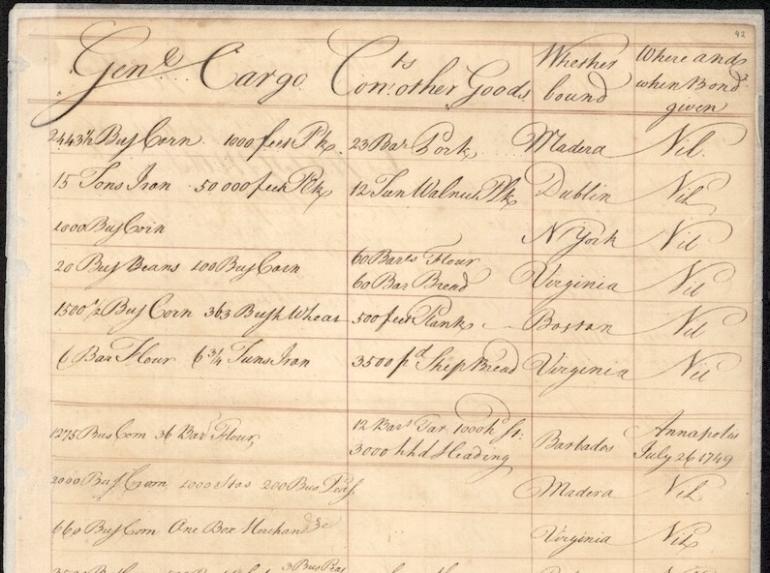

The Baltimore Iron Works was quite profitable, even though the absentee owners frequently argued amongst themselves and failed to provide enough food or replacements for the depleted workforce. Each owner got one-fifth of the pig iron to sell through his own agent and shipping method. During good years, the partners made a 55% annual return.

Generational Wealth

The ironworks prospered and was one of the few colonial firms entrusted to provide iron for cannons and munitions for the Continental Army during the Revolution. However after the war, the ironworks lost many of its English customers who chose to boycott American products. By 1799, the Baltimore Iron Works had ceased production and was leasing its equipment to an anchor and nail manufacturer. In 1810, the remainder of its more than 30,000 acres of land and 200 enslaved people was auctioned off for 30 shareholders who had inherited portions of the original five shares.

Pouring steel at the Sparrows Point Bethlehem Steel plant, circa 1970. Courtesy of the Baltimore Museum of Industry.

Bethlehem Steel at The Point

Over its 125-year history, the steel plant at Sparrows Point became a major force in the economic and cultural life of Baltimore. Once bucolic farm land, Sparrows Point developed into a vast network of factories, docks, mills, and furnaces with a company town that ran its own police force, fire department, churches, and schools. Although the plants were not segregated, the surrounding communities were and housing for African American workers was often of lower quality than that available to white workers.

Steel Town

By the mid-1950s, Sparrows Point, then owned by Bethlehem Steel, was the largest steel plant in the world, stretching four miles and employing more than 30,000 workers. Its adjacent shipworks produced ships for two world wars.

Among the notable ships produced at the Sparrows Point shipyard was the S.S. Ancon, built in 1901-2. In 1914, it became the first ship to officially pass through the Panama Canal, inaugurating a new era of global trade.

Symbol of Strength

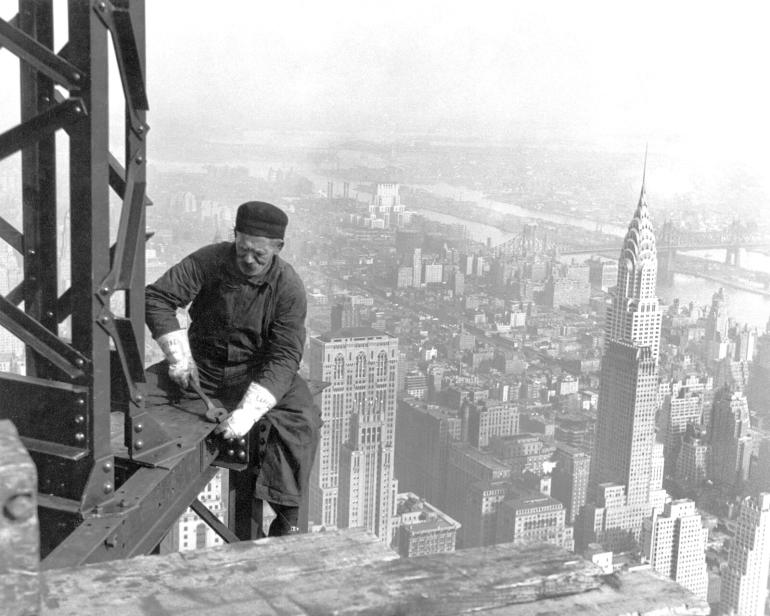

Baltimore steel was a key component in the engineering marvels of the 20th century as the skyscraper was born and vast bridges were built to connect distant shores. From the 1930s - 1950s, the Sparrows Point plant produced steel beams for the Empire State Building, as well as steel cable for the Golden Gate and the Chesapeake Bay bridges.

Shuttered and Removed

Foreign competition, technological advances, labor issues, and other industry changes exacted a heavy toll on Baltimore's Bethlehem Steel. By 2012, the plant was shuttered, and all its jobs were gone. Today, the site houses a logistics center for companies like Under Armour and Amazon.